Moodle App Development Guide

- Moodle App Overview

- Moodle App Development Guide

- Moodle App Plugins Development Guide

- Moodle App Remote Themes

- Moodle App Customisation

- Setting up your development environment

- Using the Moodle App in a browser

- Moodle App Translation

- Moodle App FAQ

- Moodle App Development Process

- Moodle App Release Notes

Upgrade from previous versions:

- See all Moodle App pages

- See pages for Moodle App Ionic 5 (current)

- See pages for Moodle App Ionic 3 (legacy)

- See pages Moodle App Ionic 1 (legacy)

- See pages for Moodle App Phonegap (legacy)

For user documentation see Moodle Mobile

| Important:

This content of this page has been updated and migrated to the new Moodle Developer Resources. The information contained on the page should no longer be seen up-to-date. Why not view this page on the new site and help us to migrate more content to the new site! |

This document contains information that developers should know before starting to code on the Mobile App. If you are only interested in developing a site plugin, you should read the Moodle App Plugins Development Guide instead.

Please notice that this documentation is useful to develop code that will be integrated in the standard app or in a custom app. Developers that want to add mobile support to their Moodle plugins don’t need to follow this.

Before embarking on Moodle-specific documentation, we recommend that you are at least familiar with Angular and Ionic Framework, the core technologies used in the application. We’ll reference any relevant concepts, but having a basic understanding will take you a long way in understanding the Moodle App.

Setting up your development environment

In order to get started, you’ll need to prepare your development environment. We recommend that you do it before proceeding with the guide, that way you can tinker with the codebase to solidify your understanding.

You can obtain a copy of the source code by cloning the public repository. If you want to work on a specific version of the app, you can check the tag with the version number you need; for example v3.9.5. If you want to work on the latest development version, you should check out the integration branch:

git clone git@github.com:moodlehq/moodleapp.git

cd moodleapp

git checkout integration # or `git checkout v3.9.5`

The only things you need to install before running the app are NodeJS and npm. Make sure that you are using the correct versions of each environment (looking at the engines entry in package.json). We recommend using a version manager like nvm to make this easier, you can prepare the correct environment running nvm install in the project root. Remember to run this every time you work with the app, or if you’re not working on any other node projects in your computer you can run nvm alias default `node -v` to make it the default.

Once you have the correct environment set up, you can run the application with the following two commands:

npm install

npm start

This will launch the application in a browser, but keep in mind that it only works with chromium-based browsers. You can read more about that in the Using the Moodle App in a browser page.

Other than this, there are different things you’ll need to do depending on what you are trying to achieve. We’ll go over some of them briefly, but if you want to learn more about this or something isn’t working as you expect, make sure to check out the full guide on Setting up your development environment.

Editing code

You can use your favorite editor to work on the application.

We recommend using VSCode as it is the one used by the core team and the repository is configured with some specific settings for the Moodle App.

The code follows the Moodle App Coding Style, and many of the style rules are enforced with ESLint. If you are using VSCode, you can automatically lint your files using the ESLint extension.

Debugging

While working on the app, you’ll want to debug what’s going on under the hood. The application uses a logging mechanism to inform of what’s happening, so if you open the console during development you will see a bunch of messages that you may find useful.

If you are working on something related with the user interface, it is useful to inspect the state of the Angular components in the page. You can do that using the Angular State Inspection browser extension.

If you are working on something that is pure logic (although it can involve components), you may want to give unit testing a try. If you are using VSCode to run the tests, you can use breakpoints right on your editor. If you are struggling to reproduce an issue in tests, you can also use breakpoints in the browser using the Sources Panel.

If you need to debug how the application is interacting with a Moodle site, you’ll need to take a look at the network requests. Most of the time using the Network Panel should suffice, but if that isn’t working take a look at the Debugging network requests in the Moodle App page.

Working with a Moodle site

When you are using the app, you’ll need to connect with a Moodle site. You may already have your own site, but using a real site may not be the best choice for development.

If you’re working on something that doesn’t need anything specific from your site, you can use a test site like school.moodledemo.net. This is a site that will reset all the data every hour, so you don’t have to worry about making any persistent change by mistake. You can also use a shortcut to log in as a student or teacher using student or teacher instead of a url. However, keep in mind that this site is also used by others who are new to Moodle, so be sensible and don’t abuse it.

If you need to configure something from the site, your best option is to run a Moodle site on your computer. Setting that up is outside the scope of this document, but we recommend using moodle-docker because it comes with everything you need (and it also supports running the app!). If you need anything specific from a course, you can always replicate it on your local site using the backup and restore functionality. You can create a backup from your production site, and restore it in your local site.

Working on native functionality

Most of the time, we recommend that you develop using a browser because it’s faster and easier to work with. However, sometimes you may need native functionality that is only available on a mobile device.

You can learn how to set up your environment by reading Ionic’s documentation for Android and iOS. The Moodle App also comes with some npm scripts used for native development. You can build and launch the app by calling npm run dev:android and npm run dev:ios.

Folders structure

In this section, we’ll see how files and folders are organised within the src/ folder.

index.html

This html file contains the shell where the application will be rendered. Before the app is ready, even before JavaScript is loaded, this is what the application will look like. In a mobile device, users will never see this because it is hidden by the splash screen until the application is ready. That’s why there isn’t any markup other than the root component that will be rendered by Angular.

You won’t see any script files referenced here because those are injected later in the compilation process. You can see the actual file in the www/ folder after running the build script.

main.ts

This file is the main entry point of the application, the first code that runs when the application is launched. The application is bootstrapped by Angular using our root application module.

You can learn more about this in the Application Lifecycle section.

polyfills.ts

This file adds polyfills for missing functionality in the platform.

app/

This folder contains the root component and the root module of the application.

You will notice that the app.module.ts file is quite small. This is because it only includes Angular and Ionic boilerplate, leaving the heavy lifting to the code within core/ and addons/.

core/

This folder contains the basic functionality of the application, and exposes pluginable interfaces for other parts to hook into. Anything defined here can be imported anywhere since it's critical for the app and it is available everywhere (in contrast to code within addons/). In order to identify code from this folder, all classes start with the Core prefix.

The core.module.ts file defines a module that imports all the core providers and modules. It encapsulates the initialisation of the application core.

The shared.module.ts file defines a Shared Module that exposes core declarables (components, directives and pipes). When other modules use any of these, it’s preferable to import this module instead of individual declarable modules separately.

There is also a constants.ts file with global read-only values.

core/initializers/

This folder contains a collection of scripts that are run within the Angular initialisation process.

These files are automatically loaded using webpack, so it isn’t necessary to import them anywhere. You can see how they are loaded in src/core/initializers/index.ts.

Keep in mind that any code placed here will delay the application startup, so it’s critical that only the essential processes are included here. If something can be initialised lazily, it should.

core/services/

This folder contains Angular services available anywhere in the application.

Most of them are Singleton Services, and they can be accessed statically using their corresponding Service Singleton.

Given that services are created on demand, none of them is guaranteed to be initialised when the application is ready. So anything that’s essential for the application to run should be placed in an initializer instead. In case that the initialisation relies on a service, it can be accessed using its Service Singleton. One good example of this is the database initialisation, which is placed on an initializer but calls each service’s initializeDatabase method.

And of course, service dependencies can be declared in the constructor to use Angular’s built-in dependency management.

core/components/

This folder contains Angular components available anywhere in the application (but remember that they should be imported explicitly using CoreSharedModule). They are exposed to the shared module using their own module: CoreComponentsModule.

This folder also contains an animations.ts file with reusable Angular animations.

All components must be declared with tag selectors starting with their module namespace (core- in this case), and defined within a folder with their selector (without the namespace prefix). These component folders can contain the following files:

{component-name}.ts— Component class.{namespace}-{component-name}.html— Component template.{component-name}.scss— Component-scoped styles.

Additionally, auxiliary components that are only used locally can be defined in the same folder, starting with the name of their parent component. For example, looking at the core-recaptcha component we can find the following files:

recaptcha.ts— Recaptcha component class.core-recaptcha.html— Recaptcha component template.recaptcha-modal.ts— Auxiliary modal component class.core-recaptcha-modal.html— Auxiliary modal component template.

core/directives/ and core/pipes/

These folders contain Angular directives and Angular pipes available anywhere in the application (but remember that they should be imported explicitly using CoreSharedModule).

They are exposed to the shared module using their own modules: CoreDirectivesModule and CorePipesModule respectively.

core/guards/

This folder contains route guards used to control access to restricted routes.

Given that we are working with a mobile application, and not deploying to the web, users won’t be able to access urls manually. But it is still important to have proper guards to prevent potential bugs and vulnerabilities.

core/classes/

This folder contains classes that don’t fit into any other part of the application. We must be careful not to bloat this folder and turn it into a mess. There can be subfolders to group files with related functionality.

Think twice before adding anything here.

core/utils/

Same as core/classes/, but containing functional utilities instead of classes.

core/singletons/

This folder contains some core Singletons and the logic to make Service Singletons.

Other than Pure Singletons, there are also some third-party services exposed through Service Singletons. However, service Singletons for application services should be declared in the same file where the service is defined.

core/features/

This folder contains Domain Modules for core features. Each of those modules encapsulates the functionality for a given area. Even though they can rely on each other (because anything within core is globally accessible), it should be avoided to reduce coupling.

The features.module.ts file defines a module that imports all feature modules.

Each feature module will be different, some may only provide services while others define routing endpoints (or both). In any case, each feature is encapsulated into its own folder.

When a module needs to export something, it has a file in its root folder named {feature-name}.module.ts defining the main feature module.

If a module uses lazy loading, that will be declared within a different module defined in {feature-name}-lazy.module.ts, and the lazy routes are exposed through the main feature module. In this way, the knowledge of which routes are loaded lazily is encapsulated within each feature folder.

Sometimes, it’s possible that a feature allows nested routes to be defined from other modules. For example, the mainmenu feature allows other modules to add extra tabs. In those situations, these features will also have a {feature-name}-routing.module.ts file.

You can learn more about the contents and motivation of these files in the Routing section.

In addition to these files, feature folders may contain the following:

{feature-name}.scss— Reusable styles for components defined in this module.classes/— Same as core/classes/.utils/— Same as core/utils/.components/— Same as core/components/ (with the core-{feature-name}- namespace).directives/andpipes/— Same as core/directives/ and core/pipes/.lang/— Same as core/lang/.services/— Same as core/services/.pages/— Page folders have the same structure as core/components/, but in addition they often declare modules as well to allow lazy-loading the page. In some cases, they can even have their own routing modules. For example, look atcore/features/mainmenu/pages/home/home-routing.module.ts.

In order to distinguish code from each feature, classes will be prefixed with the feature name. For example, the home page component declared in core/features/mainmenu/pages/home/home.ts is called CoreMainMenuHomePage.

addons/

This folder contains Domain Modules for additional features. Its structure is similar to core/features/, but the namespace is addon-{addon-name}- and addon modules are decoupled from core and each other. This means that any code within core shouldn’t import anything from addons, and addons shouldn’t import anything from each other.

This level of decoupling can be achieved using the Dependency Inversion Principle, which in this case is easier to apply using Angular’s Dependency Injection framework. However, this theoretical nirvana has not been achieved in the current status of the codebase. And it’s arguable whether it is desirable, given the cost of adhering strictly to this pattern.

For example, calendar blocks defined in the block addon import a provider declared in the calendar addon. This violates the dependency inversion principle, but it’s a sensible decision to avoid complicating the code in excess.

The end goal is to make each addon as independent as possible, keeping practicality and simplicity in mind.

In order to distinguish code from each addon, classes will be prefixed with Addon + the addon name. For example, the private files page component declared in core/addons/privatefiles/pages/index/index.ts is called AddonPrivateFilesIndexPage.

types/

This folder contains global TypeScript declaration files.

testing/

This folder contains supporting code for writing tests, but does not contain any tests. To learn where tests are located, read the Test files section.

theme/

This folder contains general app style sheets. theme.scss is the one that will be included in the html, the rest will be imported by theme or children of this.

theme.scss— This is the main file and contains imports to the rest of the files and 3rd party styles.theme.light.scss— Includes the desired variables for the light color scheme.theme.dark.scss— Includes the desired variables for the dark color scheme.theme.custom.scss— Includes custom styles.theme.base.scss— Contains global styles, css rules that will apply across the app.globals.scss— Introduces scss functionality on the the styles and contains imports to:globals.custom.scss— Global custom scss variables.globals.variables.scss— Global scss variables.globals.mixins.scss— App customised mixins.globals.mixins.ionic.scss— Imported mixins from ionic.

format-text.scss— Contains format-text tag styles.

assets/

This folder contains source files that are not considered app code. This includes things like fonts, images, and json files; but also external libraries that couldn’t be installed using npm (for example, h5p and mathjax).

An exception to this rule is js/iframe-treat-link.js, which is a file that can be considered app code but it is injected directly into iframes without a compilation step.

File names

As a rule of thumb, TypeScript files should be named after the class or interface they export. Given that it’s discouraged to use default exports in Angular applications, it is not obvious what that is for each file. But in most cases it should be fairly easy to see. In situations where there isn’t a single relevant export, like a file exporting multiple functions, you should use a name that properly reflects the nature of this grouping.

File names should use kebab case and not include namespaces nor type suffixes. For example, if there is a service declared within core/services/ called CoreFoobarService, its file name should be foobar.ts, not core-foobar-service.ts.

If a folder contains more than one type of TypeScript file, the type of file should be added as a suffix with a dot. For example, the app/ folder contains multiple types of classes and that’s why the file declaring the root component is named app.component.ts. Most components elsewhere don’t have the .component suffix. The exception to this rule are module and test files, which must always use the .module and .test suffix respectively.

Language files

All feature and addon folders can contain a lang.json file, as well as the core/ folder. The JSON file contains all translatable string keys with the current english text. During compilation, those files will be merged into one single file on assets/lang/en.json that will contain the cooked string keys (every key of those files will be prepended with the module prefix).

An automatic process will create the rest of the language files on the assets/lang/ folder based on the Moodle translation platform: AMOS.

In order to match existing Moodle language strings with the app strings the app contains a file on the scripts folder called langindex.json. This file contains an indexed array with the cooked string keys of the app, the value of every item is the module (file name) where to find the string in AMOS. If the value contains a slash ‘/’ the text before the slash will correspond to the module (file name) and the text after will correspond to the string key on that file. If it does not contain a slash, the string key will be the last part of the cooked string key (splitting using dots .).

Test files

Tests are found anywhere inside the src/ folder, and they will be run as long as they end with .test.ts. As a general rule, they are placed in a folder next to the module responsible for the code being tested. And they mirror the folder structure.

Here are some examples:

- The utils text service declared in

core/services/utils/text.tsis tested incore/services/tests/utils/text.test.ts. - The init login page declared in

core/features/login/pages/init/init.tsis tested incore/features/login/tests/pages/init.test.ts. The test file can be directly underpages/(instead ofpages/init/) because the page component is the only file that will be tested for this folder. So it would be unnecessary to have a folder with a single file. - The root app component declared in

app/app.component.tsis tested inapp/app.component.test.ts. The test file can live alongside the component because this module doesn’t have any nested folders.

In addition to unit test files, there is also a folder at testing/ with setup and file utilities shared among all tests.

Learn more about unit tests in the Testing section.

Routing

All core features and addons can define their own routes, and we can do that in their main module. However, those are loaded when the application starts up, and that won’t be desirable in most cases. In those situations, we can use lazy loading to defer it until necessary. To encapsulate lazy functionality, we can define a Routed Module named {feature-name}LazyModule. For example, the login core feature defines both a CoreLoginModule and a CoreLoginLazyModule.

With the folders structure we’re using, it is often the case where different core features or addons need to define routes depending on each other. For example, the mainmenu feature defines the layout and routes for the tabs that are always present at the bottom of the UI. But the home tab is defined in the home feature. In this scenario, it would be possible to just import the pages from the home module within the mainmenu, since both are core features and are allowed to know each other. But that approach can become messy, and what happens if an addon also needs to define a tab (like privatefiles)?

As described in the addons/ folder documentation, the answer to this situation is using the dependency inversion pattern. Instead of the mainmenu depending on anything rendering a tab (home, privatefiles, etc.), we can make those depend on the mainmenu instead. And we can do that using Angular’s container.

In order to allow injecting routes from other modules, we create a separated Routing Module. This is the only situation where we’ll have a dedicated module for routing, in order to reduce the amount of module files in a feature root folder. Any routes that are not injected can be defined directly on their main or lazy module.

It is often the case that modules using injected routes have a RouterOutlet. For that reason, injected routes can be defined either as children or siblings of the main route. The difference between those is that a child will be rendered within the outlet, whilst a sibling will replace the entire page. In order to make this distinction, routing modules accept either an array of routes to use as siblings or an object indicating both types of routes. You can see an example of this in the core/features/courses/courses.module.ts file where some courses routes are injected both as siblings and children into the home routing module.

This architecture is not limited to feature or addon modules though, page modules can also define routing modules to allow injecting routes. One example is the core/features/mainmenu/pages/home/home-routing.module.ts file. Notice how the accompanying module does not use the -lazy name prefix, that is because page modules are loaded by their respective feature module and they are always lazy, so it isn’t necessary to make that distinction (if a page is not lazy-loaded it doesn’t have a dedicated module).

In order to navigate between routes, you should use the CoreNavigator service. It works using Angular’s router under the hood, and it takes care of all the routing specific to our application.

Most of the time, you’ll probably want to use the navigateToSitePath method, because it will take into account the current main menu tab and navigate accordingly. If the call needs to navigate to another site, it’ll also take care of all the login workflow.

If you are navigating to a specific route that is not affected by the current site nor the main menu tab, you can use the navigate method directly. This method can also be useful if you want to navigate relative to the current route, for example doing:

CoreNavigator.navigate('../');

Other than navigation, this service also contains some helpers that are not available in Angular out of the box. For example, the getRouteParam will get values from multiple sources such as query parameters or route parameters, and it also supports reading non-primitive values.

Make sure to check out the full api to learn more about the CoreNavigator service.

Singletons

The application relies heavily on the Singleton design pattern, and there are two types of singletons used throughout the application: Pure singletons and Service singletons.

Pure Singletons

Pure singletons, or just “singletons”, are plain Typescript classes whose functionality does not depend on the lifecycle of the application. These normally contain helper or utility methods that enhance existing apis or encapsulate reusable functionality.

Their implementations usually consist of a collection of static methods (so technically they are not singletons, but in practice this is easier to work with).

export class CoreArray {

static contains<T>(items: T[], item: T): boolean {

return items.indexOf(item) !== -1;

}

}

Service Singletons

Service singletons are instances resolved from the root application injector. In contrast with pure singletons, these are defined as Angular services. In particular, these should be singleton services.

The motivation behind using this pattern to access service instances is improving the development experience (easier auto-imports) and delaying the instantiation of services until they are really needed.

For example, service A may rely on service B in one method. Using Angular’s dependency management you would declare service B in the constructor of service A. In this situation, service B would be instantiated whenever service A is instantiated, regardless of the method that uses it being called or not. Given the size of the codebase, this can have a cascading effect detrimental to the performance of the application. With the Service Singleton pattern, service B would only be instantiated when the method that uses it in service A is called.

To adopt this pattern, the only additional step in the service definition is to use the makeSingleton method (make sure to declare it as provided in root):

@Injectable({ providedIn: 'root' })

export class CoreUserService {

// ...

}

export const CoreUser = makeSingleton(CoreUserService);

This method will create a proxy that will relay all the method calls to the service singleton instance. This proxy can be used like you would use an injected instance of the service. When any method is called, the underlying service will be initialised lazily. If you need to access the actual instance, you can do it via the instance property.

Since they are normal Angular services under the hood, they can be overridden in other modules. But keep in mind that because they are singletons, they will be replaced everywhere and not just in the module where they are being defined.

Here’s one example of this overriding a core Angular service:

export class MyHttpClient extends HttpClient {}

export const Http = makeSingleton(HttpClient);

@NgModule({

providers: [

{ provide: HttpClient, useClass: MyHttpClient },

],

})

export class MyModule {}

This pattern can be used mostly everywhere, because the underlying system is initialised before the app initialisation begins.

The exception to this rule is within service constructors, given that we don’t have absolute control over when Angular will create service instances. For this same reason, code intended to run on application startup must be placed on an initializer. And anything else within a service should be initialised lazily, instead of using the constructor (a general good practice in programming is that constructors shouldn’t have side-effects).

In the rare cases where a constructor really needs a dependency, it’s always possible to fall back to Angular’s built-in pattern of declaring dependencies in the constructor.

All the nomenclature can be a bit confusing, so let’s do a recap:

- Singleton Service: An Angular service that will be instantiated at most once in the entire lifecycle of the application.

- Service Singleton: An instance of a Singleton Service.

- Singleton Proxy: An object that relays method calls to a Service Singleton instance.

Application Lifecycle

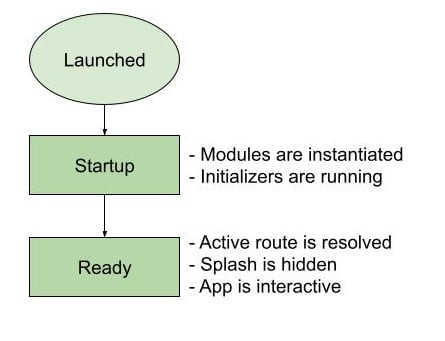

When the application is launched, the contents of index.html are rendered on screen. This file is intentionally concise because all the flare is added by Javascript, and the splash screen will be covering the application UI until it has fully started. If you are developing in the browser, this will be a blank screen for you given that the splash screen is not available on the web. We are not targeting browsers in production, so it’s acceptable to have this behaviour during development.

Before the UI is rendered, the startup process will take place. First, Angular will instantiate AppModule and all the imported modules (features, addons, etc.), and then it will execute the initializers (this includes all the initializers, not only the ones declared under core/initializers/). In our application, we have overriden Angular’s initialisation service to get a hold of the root injector so that we can safely use the Service Singletons pattern within initializers. However, we should avoid this pattern within constructors, because those can be called during the instantiation phase.

Once the application has finished starting up, the router will resolve the active route and the corresponding page component will be rendered. At this point, the splash screen will be hidden and the app is interactive.

Testing

There are two types of tests in the mobile app.

Unit

Unit tests are written in JavaScript using jest. If you want to create a new one, jest is already configured and you only need to create a file ending with .test.ts within the project. If you’re going to do so, remember to follow the file location conventions.

You can run the entire test suite using the npm test command. If you are using VSCode, you can also use the debugger to run preconfigured test tasks in the current file or the entire project (using F5 with the default keybindings). This will allow you to use breakpoints and other advanced debugging tools.

You can write standard jest tests for the most part, but something to keep in mind is that the codebase relies heavily on Service Singletons. So you will need to mock any instances that are used in the code you’re testing.

You can learn more about this in the Unit testing for the Moodle App page.

Acceptance

Acceptance tests are written in Gherkin using Behat. These are run against the full application with a real Moodle site, so they are more heavy-handed and will take longer to run. But they are also much more realistic than unit tests.

If you are using moodle-docker, you can configure it to run the tests from your local copy of the application. Keep in mind that doing this will run the app on a docker image, and expose the dev server to your machine. So you shouldn’t be running npm start or any other commands launching a dev server while docker is running, or you’ll have two instances running and that can cause some problems.

In order to run your Behat tests, they need to be installed in the Moodle site. You can automate this process by running the npx gulp behat command in the app folder, which will create a local plugin containing your application tests. This uses the environment variables from moodle-docker, if you're not using it you can also configure this by setting the MOODLE_APP_BEHAT_PLUGIN_PATH variable. If you want to keep them up to date every time you change the test files, you can run npx gulp watch-behat (this is already done when developing locally, but if you're serving the app with moodle-docker you'll need to run this from your local machine).

You can write standard Behat tests for the most part, but there are some steps specific for the Moodle App that you should use instead of the ones for the Moodle LMS.

You can learn more about this in the Acceptance testing for the Moodle App page.